Who They Were

Who They Were

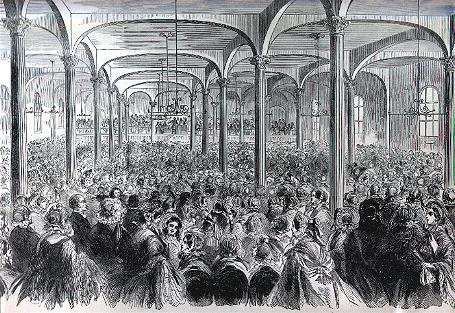

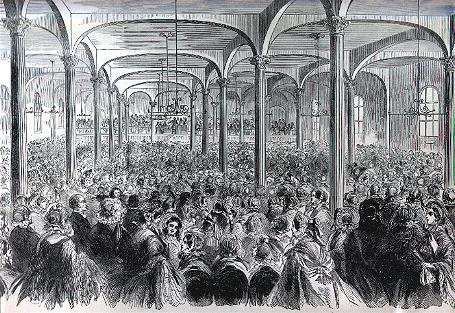

"Women's Meeting at Cooper Union Hall, Cooper Institute, New York City, to organize the 'Woman's Central Association of Relief' for the Army," from Harper's Weekly. Any of these women could have become nurses.

(From the collection of Shaun Grenan)

"And who were they all? -- They were many, my men:

Their record was kept by no tabular pen:

They exist in traditions from father to son.

Who recalls, in dim memory, now here and there one. --

A few names were writ, and by chance live to-day;

But's a perishing fast fading away."

(from "The Women Who Went To The War" by Clara Barton)

Although we may never be able to document every female nurse who served during the

Civil War, we can make a few generalizations regarding who they were. For the most part, they came from comfortable, middle class families. The majority of these women were well educated. They were "old stock" Americans, many claiming to be descendents of Revolutionary War veterans. Few nurses were of foreign birth, except for many of the Catholic Sisterhoods who also volunteered their services. Similarly, the accounts of female African-American nurses have been greatly neglected. However, individuals such as Harriet Tubman and Susie King Taylor have been well documented cases of black nurses. Regardless of their backgrounds, these women were all swept up in the patriotic fervor that followed the bombardment of Fort Sumter. Just like the men around the country, women also desired to show their support for the War.

Nursing the sick and wounded was one way for women to prove themselves during the War. Most of them volunteered their services, not always expecting to be paid for their work. Others were sent by state agencies or aid societies. Many in the northern states were assigned by the Superintendent of Nurses, Dorothea Dix. Others, yet, followed their husbands, fathers, or sons into the army. Some women were not necessarily recognized as nurses even though they performed similar duties. Selener Richards, for example, was awarded the title of superintendent of the Diet Kitchen. Marie Tepe was the vivandiere of the 27th and later the 114th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, but she also worked at the field hospitals following the battles in which her regiment was engaged.

Even though Dorothea Dix required that her nurses be over 30 years of age, we find a few instances of younger women working under her supervision or finding appointments in other manners in the North. It has been documented that Dix assigned women to positions who were much younger than 30, especially towards the end of the War when help was greatly needed. Elizabeth C. Perkins was able to follow the 11th Maine Vols. Inf. as a nurse even though she was only 22 years old due to her strong "character" and "reliability," in Dix's words. In the South, there were no strict age requirements for female nurses. Therefore, the ages of nurses ranged greatly in the North and South - from young teenage women to more mature adults. On the one hand, Annie Etheridge was merely 17 years old when she attached herself to the 2nd Michigan Vols. Inf. as a nurse. Abigail H. Gibbons, on the other hand, left her work in New York City at the age of 60 to volunteer in the hospitals near Washington when the War started. For the most part, though, nurses seemed to be between their late 20s and early 40s, many having been married as well.

As we have seen, the female nurses of the Civil War were not a superior breed of being. They were average but strong willed women who wanted to make a difference despite the societal rules which reigned over their lives. By becoming nurses, they left their marks on American history.

Back to

Copyright 2002 by Britta Arendt